My friend Geoff lives on the Isle of Wight, so I only see him when he passes through London on his way to France. “I saw a sign in my local metal works,” he said, the corners of his mouth twitching. He waited a few suspenseful seconds then announced solemnly, “Leysdown… Where Time Slows Down.” We both laughed, because actually Leysdown is where time stands still.

Leysdown on Sea. Birthplace of British Aviation.

Most people have preconceived ideas about the Isle of Sheppey, usually negative ideas! But 100 years ago Leysdown, at the eastern end of the island, was at the cutting edge of technological innovation. Today Leysdown is a backwater stuffed with holiday camps and amusement arcades and only comes alive in the summer. If you take the road east from Leysdown towards Shellness, you pass one final holiday camp at Muswell Manor then 300 hundred yards further on the road ends and a rutted track begins. This is Shellbeach.

Leysdown is an unlikely location for ‘firsts’ but this month is the 103rd anniversary of the first flight by an Englishman in Britain, by 25 year old John Moore-Brabazon, on the 2nd May 1909.

JTC Brabazon’s ‘Bird of Passage’ outside the Short Bros works, Shellbeach.

In 1908 the Short Brothers, who had a factory in Battersea building balloons, looked around for more space so they could experiment with the new flying machines. They established a small aircraft factory at Shellbeach, the first of its kind in the world. With the world’s first purpose-built aerodrome. Nearby was Mussel House (now Muswell Manor) the HQ of the world’s first flying club, the Aero Club of Great Britain.

Charles Rolls drove Wilbur and Orville Wright to Shellbeach. The chauffeur was a passenger! May 1909.

A couple of days after Brabazon’s epic flight the Wright Brothers arrived at Shellbeach to meet the Shorts and discuss licencing Short Brothers to build Wright Flyers. They had their picture taken outside Mussel House with Brabazon, his friend Charles Rolls, and Frank Maclean.

The Wrights with the Shorts, and Charles Rolls, JTC Brabazon, and Frank McClean, outside Muswell Manor, Shellbeach. May 1909.

The Daily Mail put up a prize of £1,000 for the first Englishman to fly a circular mile, and in October 1909, Brabazon’s Short No. 2 biplane was launched from rails and flew the circular mile at a height of about twenty feet. Six days later he took a piglet with him in a basket. The first flying pig! In March 1910 Brabazon received the world’s first pilot licence, Charles Rolls received the second. Three months later Rolls made the first two-way Channel crossing in a Wright Flyer built by Shorts.

Charles Rolls flying a Wright Flyer manufactured by the Short Brothers at Shellbeach

Frank McClean offered the Navy two planes for pilot training and so the Royal Naval Air Service, the forerunner of the Royal Flying Corps and the Fleet Air Arm came into being at the new Shorts factory at Eastchurch, a mile or so from Shellbeach. In 1912, in Sheerness Harbour, a Short S27 was the first plane to takeoff from a ship in Britain. After the 1st World War Shellbeach was abandoned as a flying ground, the action moved to Eastchurch. If it wasn’t for the efforts of Sharon and Terry Munns, the owners of Muswell Manor, these incredible events at Shellbeach would have been forgotten.

Site of the Shellbeach Flying Ground, Muswell Manor in the distance.

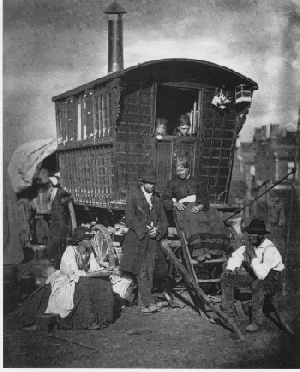

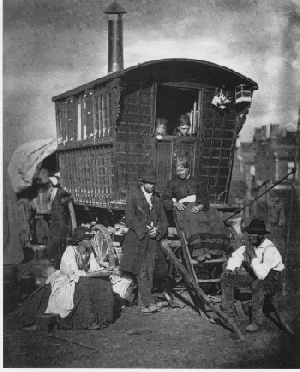

Sheppey also claims to have invented Gypsy Tart, fondly remembered (by me anyway) from school dinners, and a real regional speciality. The story goes that a farmer’s wife watching hungry gypsy children playing outside her home decided to cook them something sweet and filling with the few ingredients she had to hand. Gypsies haven’t always attracted hostility, for hundreds of years they were an accepted part of the countryside and an important itinerant workforce for farmers.

19th Century Gypsy Family with their Caravan

In the winter months they headed for London; by the 17th and 18th Centurys there were large groups of gypsies in Notting Dale, Walworth, and around Seven Dials in Covent Garden. The biggest gypsy encampment near London was in Norwood, the ‘Great North Wood’ recorded since 1272, which stretched from Selhurst to Deptford. The wood was also home to charcoal burners and farmers, and since Henry VIII’s time used for timber for the Navy. The section of the wood near Ladywell known as Bridge House Farm was set aside to provide wood to maintain London Bridge. As late as 1891, twenty gypsies were recorded at Bridge House Farm in the census, in addition to farmer Daniel Phillips’ family.

Margaret Finch, Queen of the Gypsies. Norwood.

The most famous Norwood gypsy was Margaret Finch, the Queen of the Gypsies. She lived in a hovel made from branches and lived to 108. Her fortune-telling drew huge crowds including Samuel Pepys and his wife. Coincidentally Pepys’ cousin Thomas owned a section of the Great North Wood in Hatcham, Deptford. Fortune-telling was an accepted part of gypsy life. In 1668 Pepys wrote in his diary, ‘This afternoon my wife and Mercer and Deb went with Pelling to see the Gypsies at Lambeth and have their fortunes told; but what they did, I did not enquire.’ Perhaps he was nervous of gypsy curses? Five years earlier walking near Deptford with a friend he’d met some gypsies. He wrote in his diary, “in our way met some gypsys, who would needs tell me my fortune, and I suffered one of them, who told me many things common as others do, but bade me beware of a John and a Thomas, for they did seek to do me hurt, and that somebody should be with me this day se’nnight to borrow money of me, but I should lend him none. She got ninepence of me. And so I left them and to Greenwich and so to Deptford.“

I’ve met quite few mediums, astrologers, and psychics over the years. I’m a confirmed sceptic, I don’t believe in ghosts, spirits, poltergeists, or astrology. My ‘believing’ period happened in my mid to late teens. I believed in flying saucers, that the pyramids were constructed by aliens, that houses could be haunted, that poltergeists threw things around, and that the ‘I Ching’ was a book full of wisdom. Every year I consulted ‘Old Moore’s Almanac’ and believed in Nostrodamus’ predictions. Haunting my local library I read everything I could lay my hands on about flying saucers. ‘Chariots of the Gods‘ by Erich von Daniken was the book we all read at school and quoted endlessly.

Borley Parish Church, Essex. ©Oxyman/wikimedia commons

Then I discovered Harry Price. Mr Price had written a book called, “The Most Haunted House in England: Ten Years’ Investigation of Borley Rectory“. He was a local man schooled in New Cross, and for a while he lived on Harefield Road in Brockley. He made his reputation exposing fraudulent mediums, but went on to be discredited as a psychical researcher.

Harry Price and Ghostly Companion.

Harry Price wrote about a dozen books and I read most of them, sometimes waiting weeks while the library tracked them down. His year-long ‘psychic investigation’ of Borley Rectory made him famous, and one wintry day we made an excursion to Borley. The rectory was long gone destroyed in a fire, but the church was suitably spooky, with Tim Burton-esque yew trees cut into fantastical shapes. The church is a place of pilgrimage for the many Harry Price fanatics, and there is a thick visitors’ book. I found an entry: “Harry Price was a charlatan.” And so he was.

Shellbeach, Nella Jones Old Hut.

At Shellbeach is a sad abandoned shack. This belonged to the famous psychic Nella Jones. I met and photographed Nella once at her home in Bexleyheath for ‘Woman’ magazine. I’ve met so many mediums that I’ve become a bit jaded about working with them, they can be hard work. Most want to impress you with their powers, and constantly ask questions that just might lead to some revelation instead of getting-on with the reason I’m there, to take their picture.

Mystic Meg and her Psychic Telephone

For a while I freelanced for ‘Sunday’, the News of the World’s colour supplement, where Mystic Meg worked as the magazine’s deputy editor. She’d changed her name from Margaret Lake to Meg Markova. I had the impression the staff were frightened of Meg, she hardly ever spoke, and when she did it was in a strange whispered monotone. She had the whitest skin I’d ever seen, and seemed to glide silently around the office without touching the floor. One day I was at the lightbox joking with the picture editor when Meg appeared silently by my elbow. “I like this man,” she whispered and glided away. Soon after I was asked to shoot new pictures for her column, this was considered a great honour because Meg had always insisted on starry photographers. The great day arrived, I photographed Meg with her crystal ball, with a black cat, and with her Mystic Telephone; an ordinary dial telephone covered with stickers of stars and moons and astrological signs. I thought it was a bit naff, but the picture editor told me the telephone was very important. This was the early days of premium telephone lines, and there were fortunes to be made.

Mystic Meg’s Horoscope Page in ‘Sunday’.

Another friend was made redundant, and starting a new career as a literary agent she began representing an astrologer. Under her guidance he went from a weekly column to a national daily. Then came the notion that people would pay to hear recorded horoscopes; it would take a large investment, all her redundancy pay, to set up the operation and record the horoscopes but the returns might be worth it. My friend asked her accountant for his opinion. “Don’t take the risk,” he implored her, “you’ll lose everything.” She ignored his advice and now she’s a millionaire. There was a boom in psychic magazines: ‘Spirit and Destiny’, ‘Fate and Fortune’ and so on, and the womens’ weeklies ran a spooky feature at least twice a month. For a while there were endless weird stories to be photographed: the ex-policeman with the poltergeist in Surbiton who told us about the ghostly motor-cyclist in the Tolworth underpass; the woman near Heathrow with the spirit that carried cans of beans across her kitchen (cue Clarissa and beans suspended from a fishing rod); the couple in Derby who insisted a Roman Centurion vacuumed and did the washing-up, (cue Clarissa again, with vacuum hose suspended from the fishing rod); the family who heard ghostly Spitfires taking off; and the woman in Dagenham who sees Jack the Ripper in her mirror. I became blasé about council houses built on monasteries, and the endless stories of tunnels linking modern maisonettes to the nearest graveyard.

The Wild Cattle at Chillingham Castle, ‘The Most Haunted castle in England’

Otherwise hard-headed editors were willing to believe anything it seemed. Off I’d go trying to inject a bit of spine-chilling drama with coloured gels and Hammer house of Horror lighting. Some of these stories never appeared, there simply wasn’t anything to them. I spent all night with two ‘ghost hunters’ at Chillingham Castle in Northumberland, which the owners claim is the ‘most haunted in England’. Well it is built on an old monastery, and is a favourite with TV ghost shows. My ghost hunters became hysterically excited at a dot of light on the screens of their digital cameras, “It’s an orb!” They screamed, while nothing showed up on my Polaroids. The most exciting moment of a very long night came when we opened the door of one room and a bat flew round and round over our heads. Far more interesting to me were the famous wild white cattle in the grounds, unique to Chillingham.

Have you ever seen a convincing photograph of a ghost? No, neither have I and I’ve been in some supposedly rampantly haunted houses.

Rita Rogers in ‘Bella’

The editor of another magazine had received a reading from Rita Rogers, who claimed to have Romany gypsy in her blood. Rita had been Princess Di’s favourite psychic, and Diana and Dodi would fly to Rita, landing their helicopter on her lawn. When Rita became ‘Bella’ magazine’s resident psychic I went to photograph her, with Clarissa and a makeup artist. Rita lived in a big house in Derbyshire. She followed me around asking questions as I moved the lights from room to room and reloaded the cameras. “Have you been in an accident recently?” No. “Do you know anyone who’s had an accident?” No. “Someone called John?” No. I was trying to concentrate, but she wouldn’t give up. She disappeared to have her makeup touched-up. Clarissa put her head round the door of the room where I was setting-up. “She’s made the makeup girl cry,” she hissed, eyes rolling. We never found out why. I impressed Rita by making friends with her parrot. “I’m going to leave him to you when I die,” she promised, “he doesn’t usually like men.” Apparently Loyd Grossman had been filming ‘Through The Keyhole’ a few weeks before, but when he asked the parrot who was a pretty boy the bird had turned to Loyd in a world-weary fashion, looked him in the eye and said, “Fuck Off.” I liked Rita, despite all the questions she was friendly and down to earth. After we’d packed the lights away and just before we left, we sat having a cup of tea with her, Clarissa was sitting by herself on a sofa. Rita suddenly turned to her and said, “Your father is sitting next to you. His name is George.” And Clarissa burst into tears.

Bonjour Monsieur Picasso by Clarissa Porter

Sometimes mediums are so desperate to impress it can be funny. Olive in Clacton asked so many questions it was obvious what she was up to, giving up on me she tried Clarissa, who had already told her our life-story and that we’d met at art school. “Do you mind if I tell you there’s a dark man wants to talk to you?” She asked. “He’s wearing a coat of many colours and says you need to take care of your brushes, he wants to kiss your hand. His name is Picasso.” She wrote to us after our visit saying she’d seen Judy Garland with Clarissa as well! Clarissa painted a picture of herself with the ‘dark man’, Picasso.

Dame Barbara Cartland at home

I’m always surprised by the almost universal acceptance of clairvoyance and the paranormal. Years ago I was asked to photograph Barbara Cartland at home. She was in her 90s but still a formidable personality. “Take a large bunch of flowers and Clarissa, and don’t be late,” commanded the picture editor. On the day we stopped at the Wild Bunch in Seven Dials to collect a huge bouquet of roses, artfully arranged and be-ribboned. At the appointed hour we rang the bell of Camfield Place. The door was opened by one of her secretaries who took the flowers from us with what I thought was a sigh, not a sigh of appreciation more a sigh of resignation. She beckoned us into a cavernous lobby filled with urns and vases full of dusty plastic flowers. We were instructed to wait. The journalist arrived late, and the secretary told her Dame Barbara was waiting for her in another room. As she shook off her coat, the journalist turned to me and said, “I’m going to give Dame Barbara a reading first,” and she disappeared through a door pulling a large crystal ball from her handbag. An hour passed, then the secretary reappeared and told me to set up my lights in the entrance hall. “You will stand there,” she said pointing at a corner, ” and Dame Barbara will stand there,” she said pointing at the opposite corner.” I found out that Dame Barbara was an early flying enthusiast, promoting gliding and in particular towed gliders. In 1984 she received an award in America for her services to the development of aviation! Not only that but she was a life-long campaigner for gypsy’ rights. In the 1960s she lobbied for gypsies to be allowed permanent sites, and opened one of the first sites in Hertfordshire, named ‘Barbaraville’. A few months later I was sent to photograph Jilly Cooper at home in the Cotswolds. The same journalist came along, and the crystal ball was produced again.

“I dreamed I saw you dead in a place by the water. A ravaged place. All flat and empty and wide open.”

Nella Jones also claimed to be a Romany gypsy, she was known as the psychic detective, becoming famous helping the police with their enquiries and leading them to recover a stolen painting by Vermeer; she also claimed credit for guiding them to the Yorkshire Ripper. Nella was said to have helped ‘put away’ some hard men, and was rewarded with a dinner in her honour given by Scotland Yard. Unfortunately for her, one of these hard men held a grudge. The story I was told was that he wrote to her just before he was due to be released. “I know about your place at Shellness. One night when you’re asleep I’m going to burn it to the ground with you in it.” A terrified Nella never went there again, and the property was sold at auction. A friend of mine bought it which is how I heard the story. It’s changed hands a couple of times since, but still seems to have a cloud hanging over it.

My recipe is Gypsy Tart of course. I’ve based my recipe on the Kent County Council recipe with some minor changes, you can see a nice dinner lady making it here. You’ll have enough filling to make two 20 cm diameter tarts. This is a really simple farmhouse recipe, which is probably why Gordon Ramsay ‘discovered’ it and put his version into his Pub Food book. Don’t worry if the finished tart looks a bit untidy, that’s how it should be, it’s gooey, and sticky and finger-licking good! If you go to Sheppey you can always buy a homemade Gypsy Tart from the Brambledown Farm Shop. Gypsy tart is so sweet that you need something like creme fraiche to go with it, something to cut through the sweetness. English strawberries are just in and I bought some from Mersham Game at Brockley Market. They were the perfect accompaniment for the tart, which is so soft and runny that you can dip the strawberries into the tart instead of sugar.

Gypsy Tart

Gypsy Tart

Preparation time: 30 mins.

Cooking time: 40 mins.

Ingredients ( makes 2 20cm tarts):

110g plain flour

Pinch of salt

1 tsp icing sugar

50g margarine (or butter) cubed

Ice cold water

1 410g can of evaporated milk

340g dark Muscavado sugar

Method:

First make the pastry: Sift the flour into a mixing bowl with the salt and icing sugar.

Add the chopped margarine, and rub it all together with your fingertips till it resembles small breadcrumbs. Make sure all the fat is rubbed in to the flour, don’t hurry.

Make a ‘well’ in the middle and add a little cold water, working the dough with your fingers and adding water as necessary to make a ball of dough, stiff not too wet. Then wrap it in cling film and put into your fridge to chill for at least 15 minutes.

Take the dough, remove the clingfilm and on a sparsely floured surface, roll it out. It doesn’t have to be too perfect. Grease 2 tart tins. Wrap half the dough around your rolling pin and lay it across the first tin, Gently push the dough down into the tin. Then repeat with the other tin. With a palette knife trim the excess pastry dough from around the tins, a little proud of the rim. Then if you wish crimp the edges with your fingers. With a fork prick the the pastry across the base of the tins. Loosely cover the base of the tin with baking paper and weight down with scattered ceramic baking beans.

Bake in your oven preheated to 200C for 10 minute till the edges of the pastry just start to brown. Then remove the beans and baking paper and return to the oven for another 10 minutes. Then remove and allow to cool on a rack in the tins.

While that is happening, make the filling: Put the evaporated milk and the sugar into a deep mixing bowl and whisk rapidly. You can do this by hand, but an electric mixer is better. You mustn’t skimp on the whisking! At least 15 minutes! The mixture will become a light golden brown, and increase in volume.

Put the tart tins onto a baking sheet (you can do this one at a time) and carefully pour the sugary milk into the tart, so it just comes to the top of the pastry case. Reduce the oven to 180C and carefully slide the tart on the sheet into the oven and bake for 15 minutes, watch it doesn’t burn. I see the nice lady from KCC says 3 minutes, I couldn’t bring myself to do that.

Remove from the oven. The surface will have slightly set, but the interior will still be slightly wobbly, a bit like the marshes at Shellness. Allow the tart to cool on a wire rack, it will carry on setting but it will always be a bit runny .

I served mine with fresh English strawberries, guess where? Yes, Shellbeach!

©2012David Porter